Home › Forums › Antique cartridge rifles › The Sharps 50-70 carbine

Tagged: The Sharps 50 70 carbine

- This topic has 3 replies, 2 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 11 months ago by

LittleMan.

LittleMan.

-

AuthorPosts

-

-

May 17, 2017 at 22:04 #773

LittleManKeymaster

LittleManKeymasterBy the tine the American Civil War ended in 1865 the Union had amassed a huge collection of obsolete percussion weapons. They had become obsolete a little earlier with the invention of the metallic cartridge. The Union Army did have a few 56-56 Spencer rifles, but not too many. Besides, Lincoln was dead and his 1863 insistence the Army purchase lots of Spencers could be ignored. Instead the Army looked at both the possibility of converting it’s own Springfield muskets, but also the conversion of existing in their inventory percussion rifles that used paper cartridges. Several such percussion weapons existed in sizeable quantities in Union stockpiles. Among those were the Remington Rolling Block and the Sharps rifles. During the Civil War the Sharps had become a cavalry issue weapon.

In 1866 the US Army designed a cartridge called the 50-70. This would be the standard Army cartridge for the next six years. About 30,000 Sharps rifles and carbines were converted by Sharps to the new caliber and sent back to the Army. The Army also converted about 500 Remington Rolling Blocks but later abandoned that project. Converting the Rolling Blocks usually required replacing the barrels (many were in .58 or 56 caliber) and ejector but in the case of the Sharps only the breech firing mechanism needed replacement as the bulk of those were in caliber .52. Some, but not all got relined to .50 barrels, but this was cheaper than the total replacement of the barrel. In 1867 the US Navy which had it’s own procurement process decided it wanted Rolling Block carbines made in caliber 50-45 (a shorter version of the 50-70). 5,000 were purchased. Meanwhile the US Armory at Springfield had also began manufacturing the Rolling Block rifle and carbines in caliber 50-70, both for the Navy and also for field trials against the Alin trapdoor conversion of the Springfield percussion rifle.

In 1870 three major events occurred involving the Rolling Block. 7,000 of the Springfield Armory Rolling Blocks were, in a questionably legal transaction which was not blockable, Remington managed to sell 7,000 of the 1870 Springfield produced Rolling Blocks to France for use in their war with Prussia, the US Navy received another 1,000 Rolling Block rifles and 300 more carbines, all in 50-70. But devastating to the Rolling Block’s US military future was the US Army determination during the field trials that the requirement a Rolling Block rifle hammer be cocked in order to be loaded created an unsafe situation for a trooper on horseback struggling to control a horse, reload his rifle while literally dodging hostile fire. Neither the Trapdoor conversion nor the Sharps had that physical limitation. Both could be placed in half cock, and indeed in the case of the Sharps it was not even necessary to touch the hammer to reload the gun. The Army soon recalled their Rolling Blocks and sold them off as surplus. The US Navy (and the Marines) kept theirs for a few more years as being on horseback was not a usual element of a Naval action.

With the ending of the US Civil War, the US Army remained at war. During the Civil War the six ‘civilized’ tribes living on the Oklahoma Reservation had secretly signed a pact agreeing to back the Confederacy and began to take up arms against the US in total breach of their treaty with the US. As a result of the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Manassass and at Wilson’s Creek Confederate agents were able to convince Indian leaders the Northern side would lose the conflict and that the Treaties with the US would be meaningless if the area fell under Confederate control. One by one the tribes decided the Union would lose the fight. Tribes which backed the Confederate side included the Creek and the Choctaw, both of whom owned slaves and therefore found a basic commonality with the Confederacy. Albert Pike, a Confederate General, was given a command and made an envoy to the Indian territories (aka the Oklahoma Reservation) and soon negotiated a series of treaties and agreements with the various tribes.

in October 1861 Chief Ross of the Cherokee also entered into a Secret Treaty with the Confederacy in which he renounced all agreements with the US and transferred the obligations to the Confederacy. The Cherokee were also given the right to have a delegate sitting in the Confederate Congress. In return the Cherokee agreed to furnish ten companies of mounted men to the Confederate Army. The Choctaw tribes raised a battalion of troops who served in both the Territory and in Mississippi. Many Seminole Indians living inside the Oklahoma Indian Territory as well as members of the Chickasaw Catawba and Creek tribes also enlisted in the Confederate Army with the encouragement of their Chiefs. Meanwhile in other states, such as Alabama the Confederate Army offered any Indian joining their side a $50 enlistment bonus and a promise of an Enfield rifle, uniforms and any needed camp equipment. Cherokee leader Stand Watie was made a Colonel in the Confederate Army and he responded by immediately drafting all Cherokee males ages 18 – 50 into the Confederate Service. Within a few years he was promoted to Brigadier General and was considered a skilled guerilla fighter and leader and he directed many raids against US forces and civilians in the Trans Mississippi West. He also encouraged tribes West of the Mississippi to renounce their own treaties with the US and attack settlers and soldiers. His most notable success was with the Santee Sioux of Minnesota in 1862 who were experiencing problems with their Reservation trader with holding needed supplies. Finally out of frustration the Sioux attacked settlers to seize supplies. At least 500 civilians died in those attacks. In 1861 the US Army was pretty much unaware of these secret treaties.

The US Army as part of it’s own obligations under the treaties had stationed four army posts containing 750 men on the West side of the Indian Territory in order to deter raiding against the Territory by Plains Indians. After the attack on Ft. Sumter the Union ordered the evacuation of those posts as they were in Arkansas which was expected to succeed. Confederate forces from Texas soon occupied those posts. The first real indicator of trouble with the Indians themselves came in September of 1861 when Confederate Cherokee infantry under the command of Confederate Colonel Cooper attacked a column of Indians loyal to the Union heading North to Kansas killing hundreds of them. Thereafter the US found itself at war with the Indian tribes named above and Indian soldiers under Confederate command were encountered in almost every place Confederate forces were found. When the Appomatax Treaty was signed the Indians were included provided they lay down their arms and return to the Reservation. Sadly for the Indians Confederate General and Cherokee leader Stand Watie refused to surrender and months after Appomattox he and his men were still battling Union forces. By then his command included Cherokee, Seminole, Creek, and Osage Indian soldiers.

A worthwhile read: http://library.uco.edu/UCOthesis/HarrisJT2008.pdf

Major General Custer at the request of General Sheridan (who viewed all Indians as untrustworthy) was initially assigned to hunt down General Watie’s forces. By he time he arrived however Watie had eventually been captured and had surrendered those under his command. Nevertheless, his continuing to fight after being ordered to surrender by General Lee was viewed as a reason to exclude the Indian tribes from the Post Civil War Reconstruction and the tribes of the Oklahoma Reservation were viewed as hostiles. Meanwhile a vengeful political pressure was mounting against the Indians and soon their Reservation instead became the Oklahoma Territory and the Oklahoma land rush began. Nothing but conflict followed and the Indian Wars were on. Meanwhile Custer had left the Army in February of 1866, only to be pulled back in as a Lieutenant Colonel in July of the same year and placed in charge of a new unit called the 7th Cavalry under the command of General Sheridan.

Until 1873 Custer’s men were armed with Sharps carbines. The Indians opposed the railroads and westward expansion, so they had to go. One of General Sheridan’s deliberate tactics was the intentional elimination of the American Bison which served as a major resource of the Plains Indians. The 50-70 sharps turned out to be very well suited for this task. Meanwhile, until the railroads to points West were built the cities back East also wanted Bison meat and furs. Adding to the lucrative trade in fur and meat was the US Army offering a bonus and ammunition at a discount. The era of the Buffalo Hunter had begun.

The Sharps Rifle Company could barely keep up with the demand for long barreled Sharps rifles. Rifles of greater range were wanted and soon cartridges such as the 50-90 and the 50-110 followed along with better tang mounted sights. Settlers and lawmen also liked the long range capability of a Sharps.

In 1873 the Trapdoor Springfield in caliber 45-70 was adapted as the new Army caliber, but the Sharps soldiered on. Although the US Army began selling many as surplus, others were issued to Indian Scouts and tribes deemed friendly. Also although Sharps rifles in .45-70 began to appear, sales of the 50-70 remained good. Nonetheless sometime around 1880 Sharps decided .45 would be their standard caliber and caliber .50 along with other calibers became a special order item. The last Bison herd became extinct in 1883 and with the loss of the Buffalo Hunter customer base Sharps closed their doors a few years later.

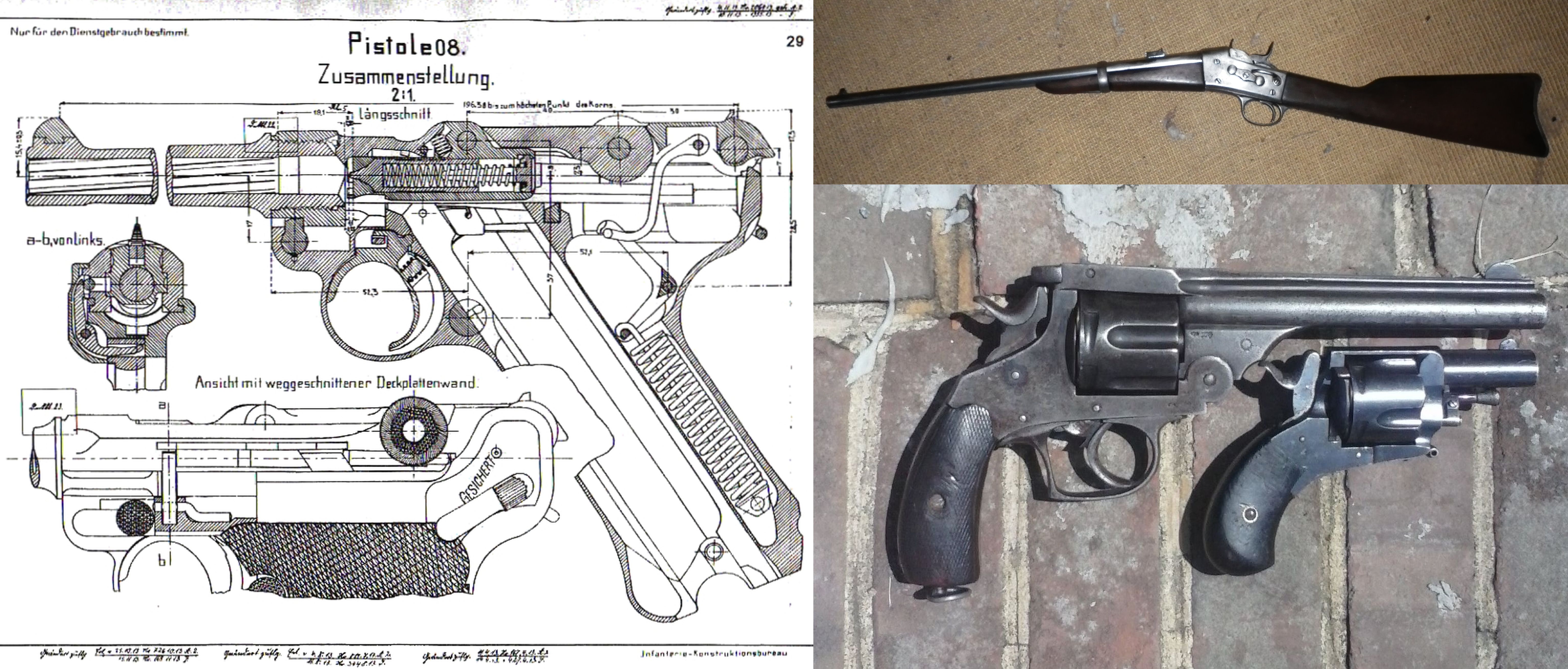

Here is a video giving a view of my own Sharps 1863 in 50-70. The serial number (in the C11,000 range) places it’s year of production as 1863. Sadly someone has replaced the wood with a new stock of the correct pattern, so their are no cartouches. The presence of a saddle ring bar confirms this was a cavalry issued item. The serial number means this carbine probably saw service in the Civil War, and it was certainly one of the ones chosen by the Army for a re-do to .50-70 which means it remained in the American military inventory for at least another seven years. Did it sit unused in an arsenal or did it do combat service against the Indians on the frontier? No one knows. Where was it in 1890 or 1920? Again, no one knows.

Here I give a firing demonstration of both the Sharps and a 19th century Remington Rolling Block carbine which is also saddle ringed (which means it was probably not one of the ones sent to any Navy). <The extraction difficulty shown by the Rolling Block is being attributed to a long ago uncleaned chamber which is now well pitted which sometimes hampers extraction.>

Your on topic comments are welcome.

-

August 1, 2019 at 18:37 #12845

Anonymous

InactiveRecently became the new owner of a nice original 1863 Sharps Carbine. Does anyone know what bullet it requires? If a comercial bullet is not availble, does anyone know what the correct mold would be. I do not want to spend 200.00 for one. I only want to shoot it a few times.

Thanks ahead of time

-

August 4, 2019 at 16:51 #12964

LittleManKeymaster

LittleManKeymasterThe gun requires black powder centerfire cartridges.

Brass is hard to get, but reloading dies do exist.

The normal load is 70grains of FF powder under a 425 gr. soft lead bullet of .512 diameter.The best (only really) place I know to obtain pre-loaded .50-70 US cartridges is the website below.

-

July 30, 2022 at 11:16 #14101

LittleManKeymaster

LittleManKeymasterThe original caliber for the 1873 Sharps carbine was .54. If I owned one of those percussion breech loaders I would probably be giving these a try.

https://www.midsouthshooterssupply.com/item/00002ac1597at/54-caliber-348-grain-aero-tip-copper-mag-power-belt-(15-per-pack)

-

-

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.