The copying of these revolvers inside the US may have been earlier than 1880, although clearly by that time both Colt and S&W were pretty upset at the lower cost, more modern, competition they now faced from Bulldog revolvers. They began popping up in the US a few years before the introduction of the Colt Peacemaker in 1873. Both Colt and S&W initially believed double action revolvers were just a fad that would pass.

With the civil war over both Colt and S&W were desperate for new military contracts. The US military was embracing the concept of a cartridge and abandoning the muzzle loader. As the US Western frontier began to open both companies scrambled to obtain military contracts and convince consumers their weapons were better.

In a decision that still haunts gun owners (and the auto industry) today the two companies began a media campaign to vilify these small revolvers of a foreign design and began sponsoring news editorials and ads labeling them as unreliable suicide specials and maintaining that only criminals used small concealable revolvers. That they themselves both marketed small revolvers was justified by claiming theirs were of superior quality and reliability (not) and used by law enforcement (sometimes). In as much as the Bulldog revolvers usually cost $2 – $4 while the Colt and Smith products ran from about $12 – $16 one can understand why American consumers often considered a Bulldog to be a better buy. Colt and Smith & Wesson begged consumers to only buy products made in America.

The American firm of Forehand and Wadsworth alone made and sold over a quarter million of the Bulldog revolvers. Iver Johnson and some other makers also introduced versions. In Belgium hundreds of small gun making shops turned these out as fast as possible and they were sold around the planet. Many American consumers bought these products, which is of course not quite the result Colt and S&W had hoped for. In 1877 Colt brought out their double action Lightning revolver to compete with the Bulldog. This was followed in 1878 by their larger Thunderer revolver to compete against the new larger framed Bulldogs which were beginning to show up on the California Coast. Those Bulldogs were now available in such calibers as .44-40 and .455 Webley in addition to the older .442 Webley, which was itself actually a short Rook rifle cartridge designed for hunting kangaroo in Australia. Colt’s problem was that by now, due to their not recognizing the wave of the future when they first saw it, several different double action revolver mechanisms were already covered by patents issued to competitors. This meant both their Lightning and Thunderer revolvers used mechanisms that were somewhat Rube-Goldbergish in design to evade patent restrictions, and they were prone to malfunctions and reliability issues that didn’t plague the Bulldogs.

Meanwhile S&W had decided to copy the 44 Webley cartridge but make it 2/10ths of an inch longer and chamber it in a top break single action revolver. Their new cartridge was called the .44 American. Although a few were sold it did not do well initially A decision was made to lengthen the case still more, change the bullet design to a non-heeled type and when a visiting Russian Duke arrived for a tour of the US in a publicity move (hoping for a Russian military contract) he was presented with one of the new revolvers, a supply of ammunition and sent him and his party on an all expense paid tour of the US. Along the way he managed to kill a buffalo with the new revolver and ever afterwards that cartridge was known as the 44 Russian.

The coming of smokeless powder and semi-automatics pushed the Bulldog revolvers into obsolescence. Many of the guns had been made in Belgium and most of their parts were made their too. Even English gun makers were known to buy their parts from suppliers in Belgium, then (like US car makers) assemble the imported cars in their country so they could be sold under the name of an English gun maker.

Although none of the Bulldog revolvers made before 1900 were really made with steels suitable for smokeless gun powder, by the late 1890s several had indeed survived trips to proof houses where they were fired once or twice with smokeless proof loads, then stamped as being tested and found safe for use with smokeless powder. History does not record how many pistols a revolver vendor would have to send to the proof house before one would manage to survive a proof test. My personal speculation is maybe one out of every 3 or 5 survived.

Since an incipient failure of the metal at the next shot does not give any warning signs before the metal yields or bursts the the presence of a nitro proof stamp on a revolver made before 1900 does not mean any use of smokeless powder is sane or wise.

Under the pre-WWI liability laws the responsibility of the gun maker ended the second the proof house passed the weapon and the gun was sold. There exist many bulldog orevolver wners who have reported the destruction of nitro proof tested Bulldogs after firing them with smokeless powder ammunition. There are also photos of destroyed Bulldogs if you care to search Google for them.

Although the European powers were desperate for handguns in the early days of WWI and many had entered the conflict with revolvers, by the end of the war all major participants favored semi-automatic pistols (mostly of 9mm or smaller caliber). Further much of the war had been fought in the same place (Belgium) the bull dog revolvers and their parts were made. No European made Bulldogs are believed to have been made after about 1916. Further, although black powder weapons abounded, most ammunition makers began making all cartridges using smokeless gun powder.

The result was many consumers either stopped shooting their old pistol and bought new ones, or the gun burst and they had to buy a new one (if they survived). Some Bulldog pistol variations of recent manufacture have been reported observed in the Khyber Pass region of Afghanistan, but of course they would not be legal to import into the US under current laws, nor are they terribly popular there compared to more modern pistol designs.

In the US .44 Webley ammunition has not been commercially available since the 1930s. However both the .44 S&W Special and the .44 Magnum use the same base cartridge case design. The rim thickened when the .44 Russian cartridge was placed in a top break revolver, but the case diameter is unchanged.

comparison left to right

.44 Webley case, .44 Special case, .44 Magnum case, complete .44 Webley cartridge

Inside the USA many American shooters in the 1880s found the recoil of the .442 Webley unpleasant and in response American ammunition makers introduced a shorter, more anemic cartridge called the 44 Bulldog which could be fired in any gun designed for the .44 Webley, the .44 American or the .44 Special. It uses a bullet of less than 170 grains of weight and only achieves about 400 feet per second (fps) muzzle velocity from a 2″ barrel. This too has been largely unavailable for many decades, although the firm of Old Western Scrounger did do a brief commercial run of the ammunition until the mid 1990s.

Upon miking the size of a slug pushed through the barrels of my 44 Bulldogs I determined both of them actually used bullets of .43 caliber. The original .44 Webley bullets were of a heeled design and weighing about 200 – 220 grains. Research determined the .44 Henry Flat also used a bullet of that design, size and weight. Indeed the 44 Henry may have been the ancestor of the .44 Rook cartridges. Bullet moulds for the .44 Henry are still available commercially as the caliber is still somewhat popular with Cowboy Action shooters. Both 44 Special and 44 magnum brass (and primers for them are) is readily available and the formula for black powder has been publicly known for centuries. Mini lathes and mills for the home suitable for working metal on 110 volt current are also available.

I therefore decided to remake some 44 Webley ammunition and bring these old weapons back to life and see if they can still dance.

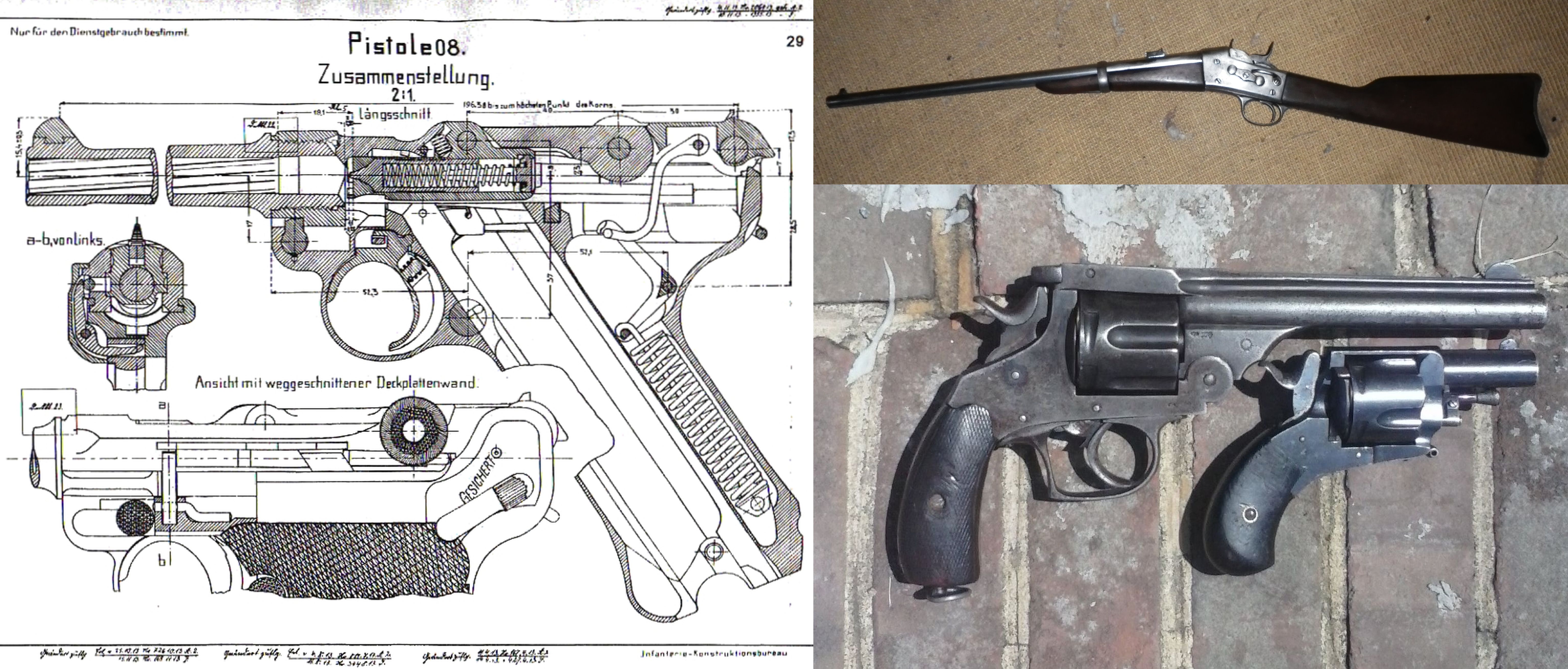

This test is to document both the accuracy and the wood penetration capability of both the 44 rounds in two different Bulldog pistols of the 1870s – 80s era. Both pistols bear a Belgian black powder proof of a type discontinued in 1892 (ELG in an oval). Neither one of them displays the rifled stamp (a capital R with a small star on top usually placed on the right side frame flat over the barrel) all pistols with rifling passing through the proof house received after 1878. One may actually be a transitional pistol in caliber 44 Webley with the Type I Bulldog frame (which emerged in 1870), but with the internal trigger mechanism of the earlier .Webley RIC (Royal Irish Constabulary) revolver and lacking the rebounding hammer feature otherwise common to all bulldog revolvers..

The wood penetration of the 44 Bulldog cartridges went about as expected as shown in the video. I had several years ago obtained and fired some of Old Western Scrounger’s Bulldog production and observed the round lacked enough power to penetrate the bark of a frozen tree. The round delivers only 83 foot pounds of energy at the muzzle which is only a tiny bit better than that of a 25 automatic pistol, such as the Browning .25. There are numerous documented cases in police files of people having been shot with a .25 who took the gun away from the person who shot them, then beat them with their own gun. Alternatively people shot with the 44 Webley tended to fall down and not move very much afterwards. Cartridges of the World and other sources state the .442 Webley bullet produces about 240 foot pounds of muzzle energy. In tests on human corpses and livestock after the American Civil War the US Army determined any bullet that can penetrate 3/4 of an inch of pine wood was potentially lethal while a bullet that could pierce a full inch of pine wood was quite capable of producing mortal wounds. As shown in the other post the 442 Webley moves a 100 feet per second than does the .44 Bulldog cartridge. I therefore tested both for wood penetration in pine boards from two different 1870s – 1880 period Bulldog revolvers.

Test results

Accuracy: Both cartridges hit the paper at or near the aiming point at 12 feet. It must be noted the folding trigger variant lacks a rear sight and is obviously intended for occasions where the time to aim is not really expected to emerge. Further both weapons are so small that only the middle finger of my right hand can fit on the grip. I would anticipate that both cartidges would be much more accurate if fired from a full size weapon such as a Ruger Redhawk or a S&W model 29 with decent sights and a grip designed for the full hand.

Penetration: Although complete penetration of the 1.5″ wood block was not achieved by either 44 Bulldog round, one of them did penetrate deeply enough to begin to emerge from the other side. Based on the US Army findings in the Civil War era this degree of penetrative ability could have caused a mortal wound in a human torso or skull. Although the first round only penetrated about an inch into the wood and was visible, in a human this too could cause a lethal wound.

The power difference of the two cartridges is plainly visible even during the accuracy test as the muzzle blast of the full power 44 Webley cartridge brushes the paper aside. Likewise. from either revolver the 44 Webley bullet just blasted through the first wood block with the first lodged deep inside the second wood block. Because the wood blocks had shifted the second Webley bullet missed the second wood block, but it too just blasted a wide path through the first block before burying itself in the ground.

As mentioned in the video I considered redoing the second penetration test, but realized the penetration of the second block was irrelevant to a determination that the cartridge is suitable for self defense use in a 5 shot small revolver of this type. It had already been established by both Webley rounds that the bullet has enough energy at 12 feet to blow through an inch or more of wood. Whether or not it could or would exit from a second identical block was immaterial. Most probably it would do as the first one did and embed itself deep inside the second block.

Conclusion:

With 44 Bulldog ammunition these weapons are best suited for paper targets or trapped mice. Bulldog pistols and spur trigger revolvers are known to have been popular with trappers of the late 19th and early 20th century as a means of dispatching an already trapped animal. I concur that they would be practical for such purpose and much safer for the trapper than attempting a throat cutting or getting close enough to bludgeon the animal.

44 Webley ammunition using bullets with a wide meplat, such as the Henry bullet is a whole ‘nother ball game. Although possessed of much sharper recoil and more muzzle blast than the .44 Bulldog ammunition, the .442 Webley cartridge also delivers 3x the muzzle energy and greatly exceeds the penetrative ability of the smaller and lighter round. In a double action revolver capable of 5 quick shots at close range as a last ditch defense it excels at this specific task it was designed for.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-bEutZOzGk

—–Suggested Reading—–

I strongly suggest that anyone thinking of converting a modern cartridge to an obsolete black powder cartridge, or manufacturing a black powder cartridge case from brass rods, etc., first do some basic reading and acquire some usable knowledge over and above watching a You Tube video which may omit showing an important step.

The process of converting or manufacturing from scratch is often more complex than simply reloading. Also because black powder is an explosive it requires some changes in procedure from reloading a modern smokeless gun powder. You should at a bare minimum have some experience with muzzle loading as well as a basic grasp of reloading concepts.

One entry level book I suggest every black powder cartridge shooter keeps in their library is “Loading The Black Powder Rifle Cartridge.” A link to it on Amazon follows so you can get a copy if you don’t have one.

A second ‘should have’ book in which much of the cartridge conversion research has already been done for you is George Nonte’s “The Home Guide to Cartridge Conversions.” It too is readily available on Amazon.com by simply clicking on the image shown below.

Anyone who shoots guns, and certainly everyone who reloads ammunition can benefit from the formula, tables and experience set forth in General Julian Hatcher’s “Hatcher’s Notebook.” This is possibly one of the most utilized reference books shooters and gunsmiths own. Available from Amazon.com via the below link.

—–Suggested tools—–

These are bare minimums, but operations such as crimping bullets into a cartridge case, properly seating primers, thinning case rims or building gauges are impossisble without them regardless if you are trying to fabricate 32 Colt brass or 44 Henry Flat cartridges.

A Loading Press. There are many makes and models. In America most use the same size dies. 7/8 inch with 14 Turns Per Inch (TPI) threads. This means that usually your dies from a Lyman press will work just fine in your RCBS press or a Lee P\press, etc.

Here is a link to a simple Lee Turret press being sold at Amazon.com. Dies and other accessories sold separately.

Mills and Lathes

It is beyond my capability here to teach you how to run a lathe or a mill. However many community colleges in America still offer courses in machine shop operations and they are worth taking if your high school did not offer similar classes. Gone are the days where the only option available was a 7 foot tall, 3 ton Bridgeport requiring a 440 Volt DC line. Today much smaller units designed for home shop use exist (called mini lathes and mini mills), and they only require 110 volts house current. They are available in many models at a variety of retailers. You will also have to buy cutters, chucks and other accessories of the proper size of course. Although there are youtube videos on the subject I again strongly urge someone thinking here of purchasing their first lathe or mill to take one of the courses mentioned first. That will give you an idea what you are doing, formally teach you best safety practices, and also the knowledge and hands on training you gain will probably save you much money when it becomes time to buy cutters, chucks, and bits.

There is no good way of thinning case rims properly without a lathe. Here is a fairly standard mini-lathe being offered for sale at Amazon.

A mini-mill is used much less often in cartridge fabrication, but when you hit a stone wall that only having your own mill can get you past, it is very nice to have one. Here is one for sale at Amazon.

Digital Calioers – Kind of a must have item. The one pictured below can give read outs in inch scale as well as metric. They are indispensable for precision manufacturing.